It was Summer 2009 when I realized that I wanted to be involved in the fashion industry.

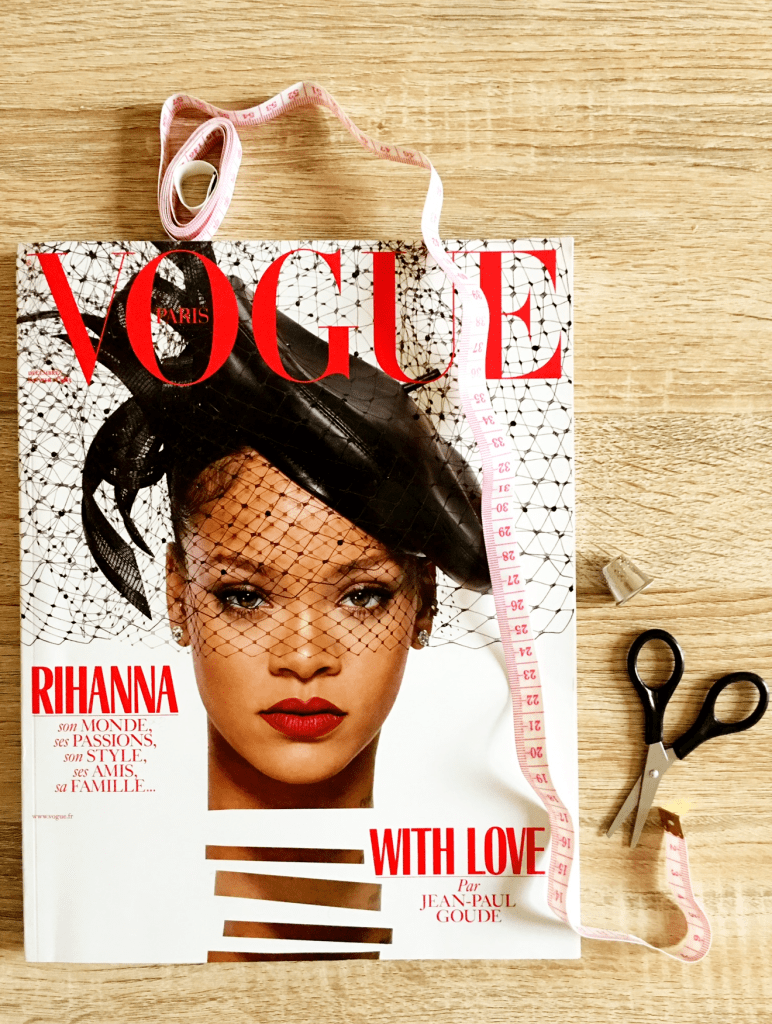

The main resources for nurturing my interest in fashion at 16 years old were taking fashion classes in high school and checking out whatever books or videos I could find at the local library.

My options were limited for where I could shop. I dreamed of the expensive brands featured in the magazines and worn by celebrities, but my wardrobe quietly betrayed me with Old Navy, Gap, and American Eagle. Meanwhile, my peers were proudly dripping in Abercrombie & Fitch and Ralph Lauren, the trendy, teenage brands at the time.

The summer I began my own independent study on fashion was life-changing.

Reading Deluxe by Dana Thomas explained what the fashion industry really was, then opened my eyes to what it could be, and how the system could be reimagined to be more sustainable and ethical, and, really, more beautiful in doing so.

The books and documentaries shared in this post helped my knowledge base to understand the history and business of the fashion industry—these authors have also published more current content.

Although there are many more resources available, including social media influencers, I think it’s refreshing and important to read well-researched books as part of your fashion education.

- Fashion Books

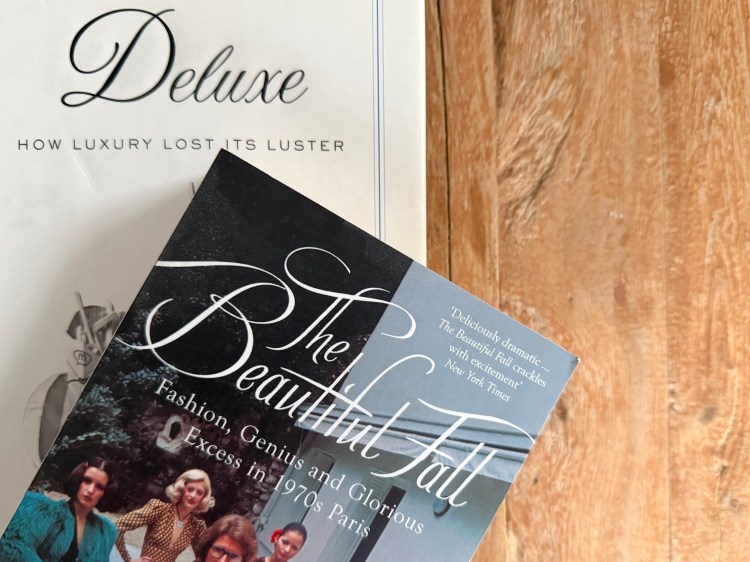

- The Beautiful Fall: Fashion, Genius, and Glorious Excess in 1970s Paris by Alicia Drake (2006)

- The House of Gucci: A Sensational Story of Murder, Madness, Glamour, and Greed by Sara Gay Forden (2000)

- The Secret of Chanel No. 5: The Intimate History of the World’s Most Famous Perfume by Tilar Mazzeo (2011)

- Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster by Dana Thomas (2007)

- Fashion Documentaries

Fashion Books

The Beautiful Fall: Fashion, Genius, and Glorious Excess in 1970s Paris by Alicia Drake (2006)

Drake exposes the lives of Karl Lagerfeld and Yves Saint Laurent, two designers who “shared the same stage, but a different destiny.” Both Lagerfeld and Saint Laurent were visionaries in the business, tried to move away from their bourgeois pasts, but the similarities end there.

One worked for Balmain for a brief stint, while the other designed at Dior and was already heir to the fashion house.

One chose to fall in love, while the other chose his work.

One a “styliste,” the other a “creator.

For decades, the Lagerfeld and Saint Laurent crowds respected each other, but a schism between the groups still remained—an unspoken competitive air pushed them apart. The author does a phenomenal job chronicling the journeys of these two fashion legends. After reading, you’ll see how Lagerfeld and Saint Laurent greatly contributed to the fashion world as we know it today.

The House of Gucci: A Sensational Story of Murder, Madness, Glamour, and Greed by Sara Gay Forden (2000)

Before there was Dolce and Gabbana (1985), there was Versace (1978). Before Versace was Fendi (1925). Today, Gucci (1921) emerges as one of the oldest and most powerful Italian fashion houses.

In 1960, Gucci was one of the first Italian luxury brands to enter the United States. Guccio Gucci founded the luxury leather goods company after travelling to England and working at the Savoy in London. He had observed the wealthy clients and understood that material items displayed one’s status–a suit, a tie, a dress, a few (or a number of) pieces of luggage. Over time, Gucci would employ his children to work for the company. He wanted his children, especially his sons, to understand the business from the ground up. Gucci’s explosive temper and domineering presence, however, would drive his children to compete against one another.

The patriarch managed to pass on the tradition of competition to his descendants. The competitive drive would serve Gucci well in some ways—the brand expanded out of sleepy, provincial Florence to Paris, London, Tokyo, and New York. Gucci would manufacture signature loafers, silk scarves, and handbags made of bamboo in addition to their trademark leather handbags crafted by artisans in Via delle Caldaie, Florence.

But the pressure to succeed would raise the emotional and financial stake of Gucci. The ever-changing international business landscape of the late 1980s and 1990s would test the endurance of the Gucci family members and their company.

On September 23, 1993, Maurizio, the last Gucci left standing in the company, signed his shares away to InvestCorp and handed over his family’s brand, three generations old.

On March 27, 1995, Maurizio was murdered.

Forden exposes the familial and professional tensions that haunt Gucci’s past. The battles between fathers, uncles, cousins, and brothers. Husband and wife. The war to keep Gucci in family hands and outsiders at bay. The constant desire for control. The thirst for power. The hunger for riches.

Today, Italian luxury brands captivate the fashion world with a sense of youth, sensuality, and modernity. The vision brought to life by Dawn Mello, Tom Ford, Domenico De Sole, and the last real Gucci left a lasting legacy on what fashion is today. The successful combination of creative direction and assertive business is a model other luxury brands have used to improve their operations.

But there is only one Gucci.

The Secret of Chanel No. 5: The Intimate History of the World’s Most Famous Perfume by Tilar Mazzeo (2011)

Mazzeo makes the objective of the novel clear: this is not the biography of Coco Chanel.

This is the story of her creation that would exceed her expectations for success. The magical scent contained in a simple pharmaceutical flask.

Over time, the bottle would go through changes. The original bottle had rounded edges, but in an effort to be more streamlined, the edges became perfectly linear. The material changed from crystal to a sturdier glass. These changes also represent the transformation of Coco herself. Working in competitive perfume and fashion industries hardened Coco into an assertive visionary.

Chanel sold her perfume to the Wertheimer brothers shortly after releasing it. Had she known that No. 5 would become a cultural icon, she would have undoubtedly kept the rights to it. Chanel fought for decades to win back the perfume by attempting to amend the contract between her and the Wertheimer brothers—she wanted to renegotiate her 10% share in Chanel Perfumes Co. compared to the Wertheimers’ 70% share.

Chanel would have succeeded in gaining control during World War II if not for the Wertheimer’s idea to temporarily put an acquaintance in charge while the brothers fled to the United States.

The best trivia to be taken away from this novel is that Chanel No. 5 was produced in Hoboken, New Jersey, during World War II. A business associate managed to bring over the signature jasmine from the plantations in Grasse, France, and maintain the authenticity and quality of Chanel No. 5. Meanwhile, in Europe, Chanel had taken a Nazi officer as a lover and traveled to Berlin to initiate peace talks.

During the war, soldiers–German and American– stationed in Paris would wait outside 31 rue Cambon to purchase bottles of Chanel No. 5 for their girlfriends or wives back home.

As Chanel—the person, the designer, and visionary—disappeared from view, her perfume only grew more popular. By the time World War II ended, Chanel No. 5 was a luxury commodity every woman wanted. It had come to symbolize hope that normalcy would return to their lives—and things did turn back around. The development of the middle class in the United States brought consumerism to a whole new level as people began to yearn for fine, foreign luxury.

Even as the war, the lawsuits, and the people came and went, Chanel No. 5 remained as a permanent haunting in Coco’s life. The Chanel No. 5 epidemic was out of Coco’s hands, no matter how hard she tried to ruin the perfume’s reputation. It wasn’t until her old age that she could learn to accept her loss as a woman and a designer.

Chanel No. 5 symbolizes lasting glamour. Eternal beauty. One woman’s loss.

Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster by Dana Thomas (2007)

For fashionistas who want to learn more about the designer brands they covet, Deluxe provides the perfect introduction to the behind-the-scenes look at the production of luxury goods. Thomas tours the reader around the world to factories and executive offices: factories in China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Egypt; specialty weavers in Florence, Como, Milan; flagship stores in New York, Paris, London, Shanghai; and the most extravagant shopping center located in Sao Paolo, Brazil, to name a few places.

Thomas also explores how the tycoons like Bernard Arnault, the owner of LVMH luxury group (Louis Vuitton Moet Henessy), have revolutionized the definition of what it means to own luxury. In the old days, there was no emerging middle class, only the incredibly rich and the incredibly poor. Only the rich had access to the finest fabrics and the finest jewels.

Now what was once untouchable has been democratized and “McCultured”. Anyone from the European aristocrat to the New Jersey housewife to the suburban teenager can buy into the dream. No more custom-fitted clothes. No more face-to-face with the designer. No more 100% guaranteed quality. Today, you are left to fend for yourself, searching through rows of clothing racks at Bergdorf Goodman, unless the elusive salesgirl at the other end of the store magically appears to your rescue. Luxury isn’t just for old money, but it is now accessible to the nouveau riche through free-standing boutiques, department stores, discounted outlets, and *gasp* the Internet.

That Burberry trench? Visit net-a-porter and you’re simply a few clicks away. The BCBG Max Azria gown? You can probably find it a few seasons later at a BCBG Final Cut outlet.

It’s still always nice to check out the brand’s flagship store. Just don’t check out the price tags.

All of the urban dwellers are more than familiar with the glamorous flagship stores: the mega store that represents the brand’s statement and carries all of the brand’s products from cocktail rings to couture gowns. The stores are designed by top architects, and their job is to create the lifestyle that the brand wants to inspire its consumers to live by.

The methods that designer brands employ to create this image are not so glamorous. Since the turn of the millennium, many clothing stores such as Gap, Zara, and Nike have outsourced garment production to third-world countries for cheap labor. Cheap labor, of course, means more profit for the company. Lower wages also means lower quality of life for the workers. In turn, some of these workers can be as young as ten years old, because their parents send them away to earn money for the family. Even the designer brands that brag of their excellent “Made in Europe” quality are manufactured in China, including Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Chanel, and the like, may unknowingly contribute to these horrible work conditions for the sake of capitalism.

When unethical work practices are hard to swallow, so is the fact that counterfeit goods like Fendi Baguettes and Vuitton monogram merchandise may fuel terrorist activity, like the 9/11. Next time you want to buy a cheap thrill on Canal Street in the city, just go to a suburban outlet so you know you’re not fueling the War on Terror.

Thomas shows the reader that there is something more to fashion than what the glossies on the newsstand tell you. Every stitch or zipper on your handbag tells a story—whether it involves the take-down of family traditions, organized crime, or depreciating quality. If you truly want to understand what modern luxury fashion means today, pick up Deluxe.

Fashion Documentaries

Bill Cunningham New York (2010)

Bill Cunningham New York follows The New York Times’s Styles photographer around doing his daily routine—riding on his bicycle on Fifth Avenue, capturing his subjects, sitting in the Times office placing the photographs for the Sunday Styles, and organizing his negatives in the many file cabinets in his Carnegie Hall studio apartment.

Cunningham is a saint, a philosopher, and above all, a communicator.

I hesitate to describe Cunningham as an artist because what he stands for is beyond the beautiful photographs of the city’s street style. He is a controlled fixture in a society that engorges itself in excess. He attends charity galas, but does not accept a meal, a drink, or even a glass of water. He lives in the center of the world, but he enjoys his small, yet cozy, loft in Carnegie Hall, riding his bicycle. He could demand a much higher paycheck, but prefers to live simply and modestly.

Cunningham’s simplicity and honest approach towards life are something we can all learn from. It amazes me that a man so involved with the material world, through documenting fashion trends on the street, detaches himself from those bodily pleasures. Unlike the luxurious coats he has photographed, he does not own one himself. He loves his inexpensive blue poncho that can be mended with duct tape. He does not care for fine dining, let alone eating. He claims to not have any romantic relationships.

I have come to the conclusion that certain aspects of Cunningham make him the perfect subject of a philosophic examination. Cunningham is above the pettiness of celebrity dramas. His honesty empowers him because it shows his strength in his abilities and makes him honorable. His simple way of life demonstrates his true passion for life and appreciating its beauty. Most importantly, Cunningham is genuinely content with his way of life. Realizing that happiness is life’s ultimate goal, Cunningham is willing to chase his happiness instead of consuming himself with worries over health, wealth, and security.

For those of you who are more well-versed in philosophy, I am more than aware I have clearly distorted Plato, Aristotle, and Machiavelli, but you must recognize that Cunningham embodies some of these teachings of selflessness, silent strength, simplicity, and satisfaction with life.

Valentino: The Last Emperor (2008)

The last couturier of the century and the father of haute couture in Italy, Valentino Garavani, is passionate, genius, and intense. The film follows Garavani and his business partner Giancarlo Giammetti while planning Valentino’s 45th anniversary in fashion and dealing with corporate outsiders buying out Valentino, s.p.A.

In light of Valentino’s passing in early 2026, watching this documentary reminds people of how Valentino’s spirit will live on through his legacy of true elegance and style.

The September Issue (2009)

Get a glimpse of a real Devil’s Wear Prada experience from the comfort of your couch with The September Issue, the documentary that covers the production of U.S. Vogue’s largest issue of the year. The most interesting storyline to follow in the film is the relationship between Anna Wintour, the Editor-in-Chief, and Grace Coddington, the Creative Director At-Large—the tug-of-war of influence, position, and editorial vision is the complex dynamic that is constantly at odds in a creative industry like fashion.

While the media landscape has dramatically changed since its release, The September Issue offers viewers a glimpse of how content production works.